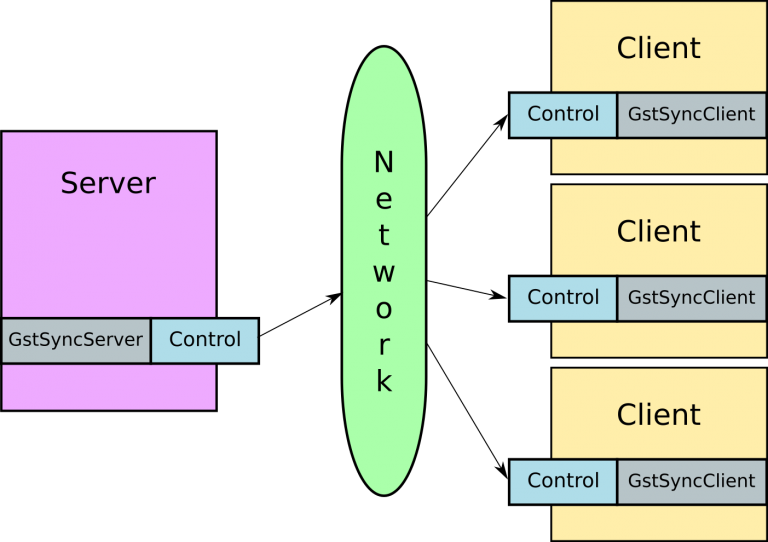

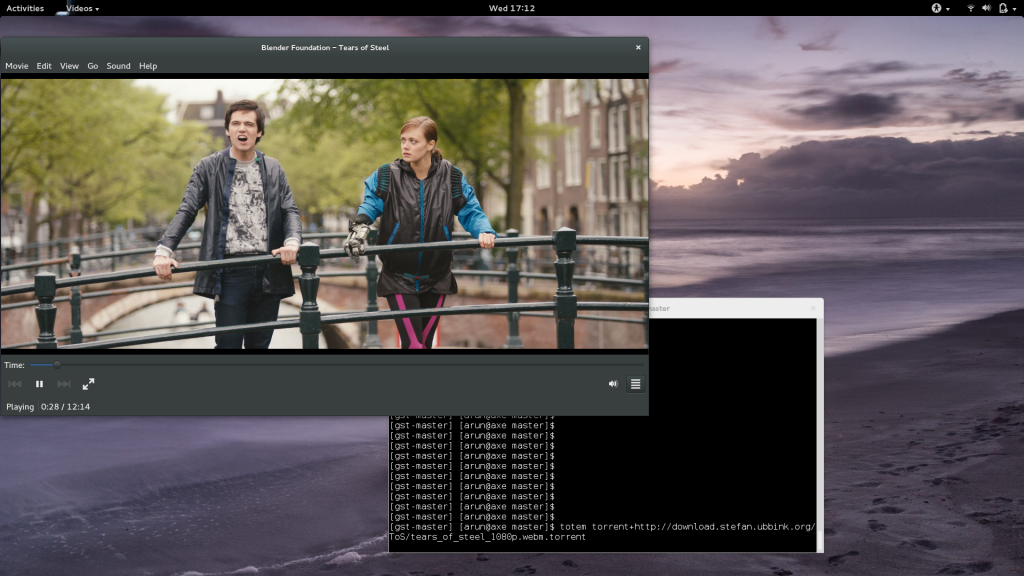

I’ve written a bit in my last two blog posts about the work I’ve been doing in inter-device synchronised playback using GStreamer. I introduced the library and then demonstrated its use in building video walls.

The important thing in synchronisation, of course, is how much in-sync are the streams? The video in my previous post gave a glimpse into that, and in this post I’ll expand on that with a more rigorous, quantifiable approach.

Before I start, a quick note: I am currently providing freelance consulting around GStreamer, PulseAudio and open source multimedia in general. If you’re looking for help with any of these, do get in touch.

Quantifying what?

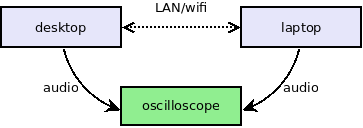

What is it that we are trying to measure? Let’s look at this in terms of the outcome — I have two computers, on a network. Using the gst-sync-server library, I play a stream on both of them. The ideal outcome is that the same video frame is displayed at exactly the same time, and the audio sample being played out of the respective speakers is also identical at any given instant.

As we saw previously, the video output is not a good way to measure what we want. This is because video displays are updated in sync with the display clock, over which consumer hardware generally does not have control. Besides, our eyes are not that sensitive to minor differences in timing unless images are side-by-side. After all, we’re fooling it with static pictures that change every 16.67ms or so.

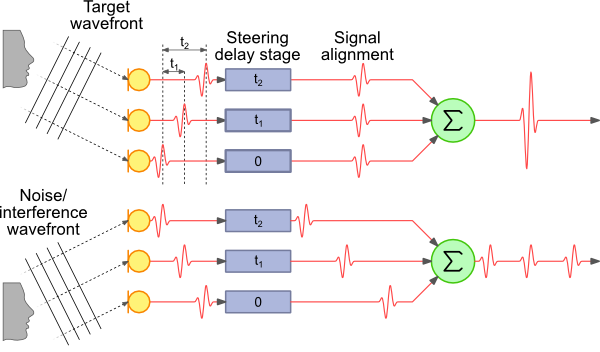

Using audio, though, we should be able to do better. Digital audio streams for music/videos typically consist of 44100 or 48000 samples a second, so we have a much finer granularity than video provides us. The human ear is also fairly sensitive to timings with regards to sound. If it hears the same sound at an interval larger than 10 ms, you will hear two distinct sounds and the echo will annoy you to no end.

Measuring audio is also good enough because once you’ve got audio in sync, GStreamer will take care of A/V sync itself.

Setup

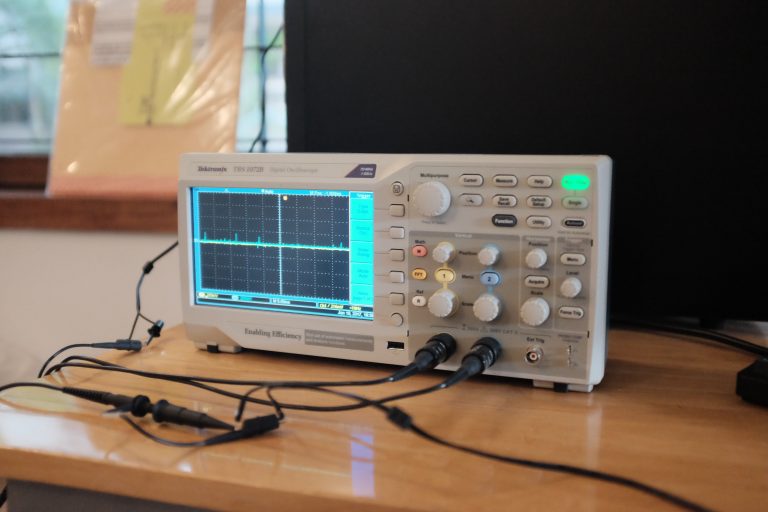

Okay, so now that we know what we want to measure, but how do we measure it? The setup is illustrated below:

As before, I’ve set up my desktop PC and laptop to play the same stream in sync. The stream being played is a local audio file — I’m keeping the setup simple by not adding network streaming to the equation.

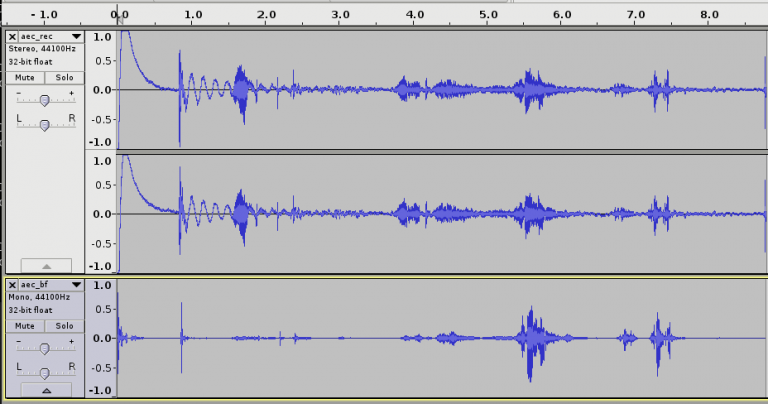

The audio itself is just a tick sound every second. The tick is a simple 440 Hz sine wave (A₄ for the musically inclined) that runs for for 1600 samples. It sounds something like this:

I’ve connected the 3.5mm audio output of both the computers to my faithful digital oscilloscope (a Tektronix TBS 1072B if you wanted to know). So now measuring synchronisation is really a question of seeing how far apart the leading edge of the sine wave on the tick is.

Of course, this assumes we’re not more than 1s out of sync (that’s the periodicity of the tick itself), and I’ve verified that by playing non-periodic sounds (any song or video) and making sure they’re in sync as well. You can trust me on this, or better yet, get the code and try it yourself! :)

The last piece to worry about — the network. How well we can sync the two streams depends on how well we can synchronise the clocks of the pipeline we’re running on each of the two devices. I’ll talk about how this works in a subsequent post, but my measurements are done on both a wired and wireless network.

Measurements

Before we get into it, we should keep in mind that due to how we synchronise streams — using a network clock — how in-sync our streams are will vary over time depending on the quality of the network connection.

If this variation is small enough, it won’t be noticeable. If it is large (10s of milliseconds), then we may notice start to notice it as echo, or glitches when the pipeline tries to correct for the lack of sync.

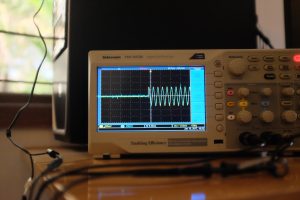

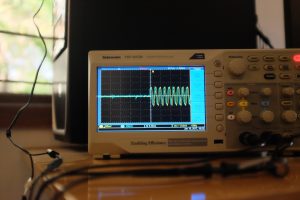

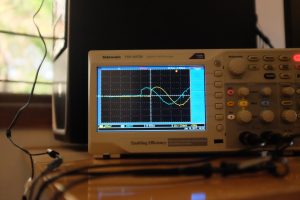

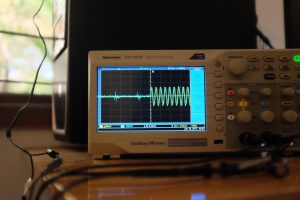

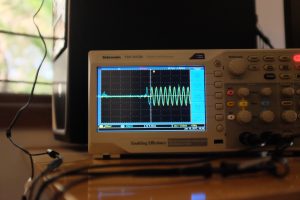

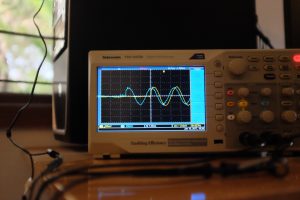

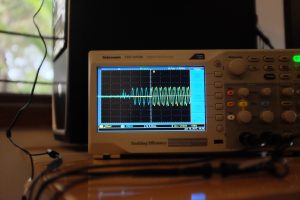

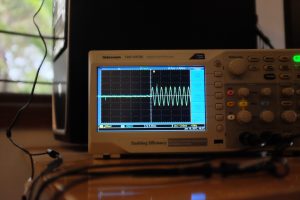

In the first setup, my laptop and desktop are connected to each other directly via a LAN cable. The result looks something like this:

- Sync on LAN, working well

- Sync on LAN, working well, up close

- Sync on LAN, slightly off

- Sync on LAN, slightly off, up close

The first two images show the best case — we need to zoom in real close to see how out of sync the audio is, and it’s roughly 50µs.

The next two images show the “worst case”. This time, the zoomed out (5ms) version shows some out-of-sync-ness, and on zooming in, we see that it’s in the order of 500µs.

So even our bad case is actually quite good — sound travels at about 340 m/s, so 500µs is the equivalent of two speakers about 17cm apart.

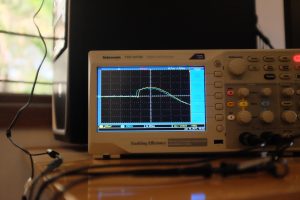

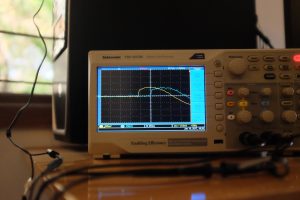

Now let’s make things a little more interesting. With both my laptop and desktop connected to a wifi network:

- Sync on wifi, okay on average

- Sync on wifi, okay on average, up close

- Sync on wifi, goes off on bad connection

- Sync on wifi, goes off, up close

- Sync on wifi, when it’s bad

- Sync on wifi, when it’s good

On average, the sync can be quite okay. The first pair of images show sync to be within about 300µs.

However, the wifi on my desktop is flaky, so you can see it go off up to 2.5ms in the next pair. In my setup, it even goes off up to 10-20ms, before returning to the average case. The next two images show it go back and forth.

Why does this happen? Well, let’s take a quick look at what ping statistics from my desktop to my laptop look like:

That’s not good — you can see that the minimum, average and maximum RTT are very different. Our network clock logic probably needs some tuning to deal with this much jitter.

Conclusion

These measurements show that we can get some (in my opinion) pretty good synchronisation between devices using GStreamer. I wrote the gst-sync-server library to make it easy to build applications on top of this feature.

The obvious area to improve is how we cope with jittery networks. We’ve added some infrastructure to capture and replay clock synchronisation messages offline. What remains is to build a large enough body of good and bad cases, and then tune the sync algorithm to work as well as possible with all of these.

Also, Florent over at Ubicast pointed out a nice tool they’ve written to measure A/V sync on the same device. It would be interesting to modify this to allow for automated measurement of inter-device sync.

In a future post, I’ll write more about how we actually achieve synchronisation between devices, and how we can go about improving it.