It’s been a busy few several months, but now that we have some breathing

room, I wanted to take stock of what we have done over the last year or so.

This is a good thing for most people and companies to do of course, but being a

scrappy, (questionably) young organisation, it’s doubly important for us to

introspect. This allows us to both recognise our achievements and ensure that

we are accomplishing what we have set out to do.

One thing that is clear to me is that we have been lagging in writing about

some of the interesting things that we have had the opportunity to work on,

so you can expect to see some more posts expanding on what you find below, as

well as some of the newer work that we have begun.

(note: I write about our open source contributions below, but needless to say,

none of it is possible without the collaboration, input, and reviews of members of

the community)

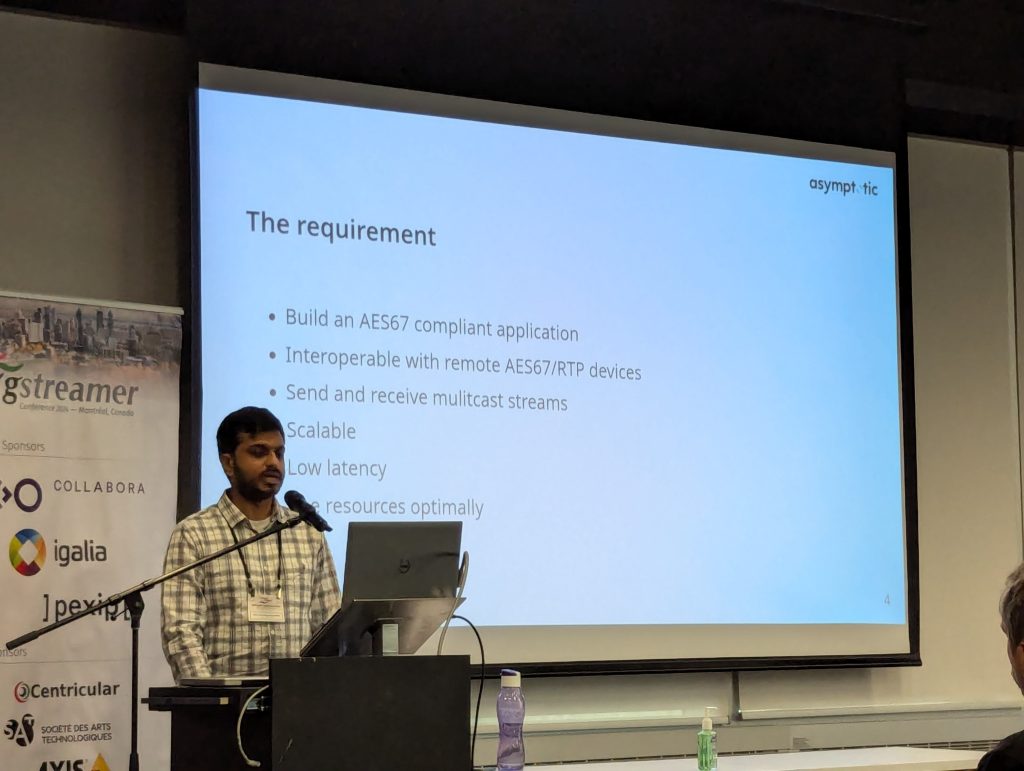

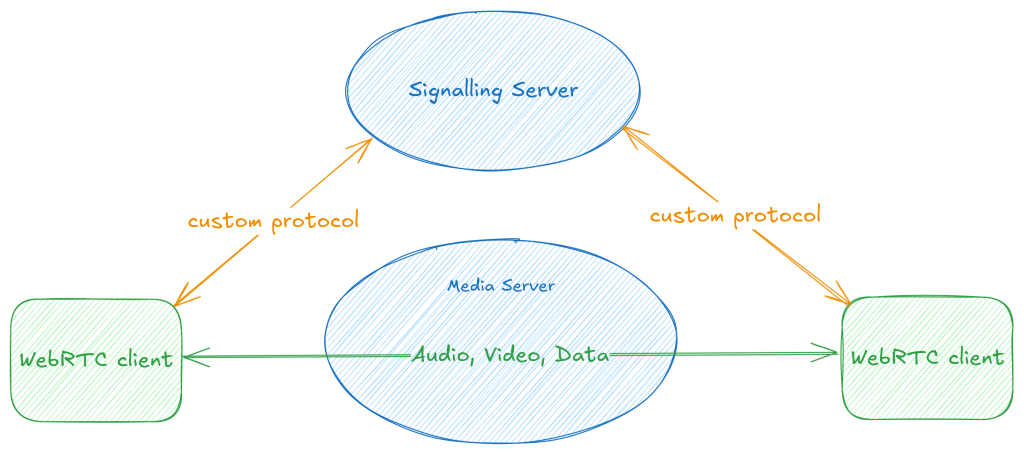

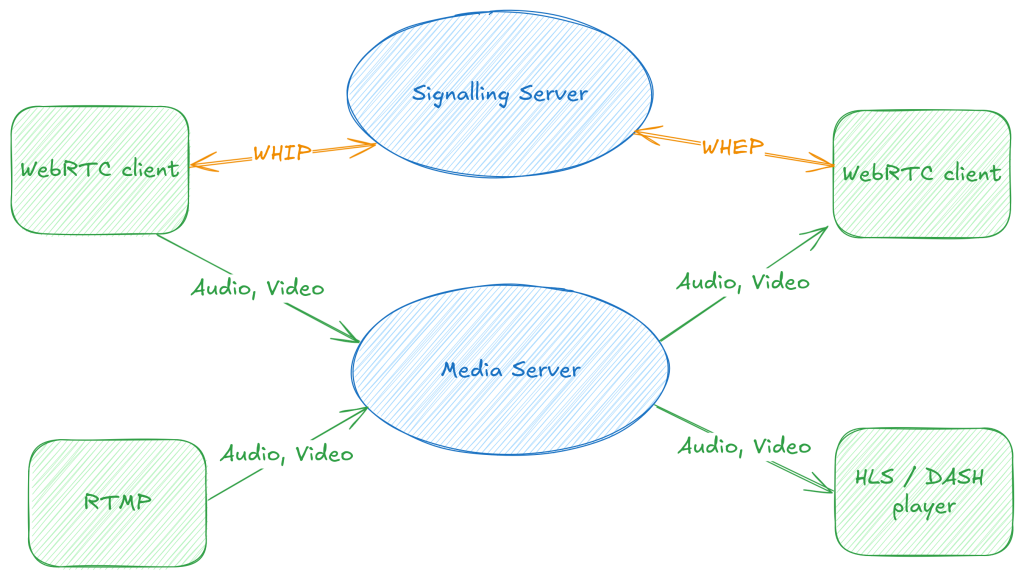

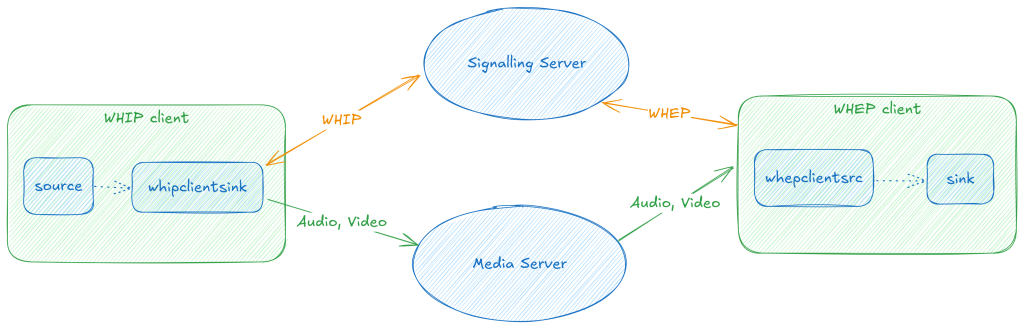

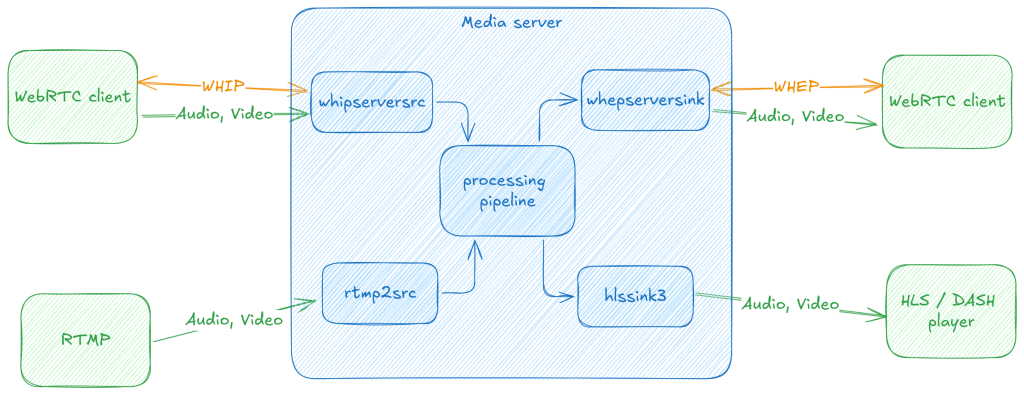

WHIP/WHEP client and server for GStreamer

If you’re in the WebRTC world, you likely have not missed the excitement around

standardisation of HTTP-based signalling protocols, culminating in the

WHIP and

WHEP specifications.

Tarun has been driving our client and server

implementations for both these protocols, and in the process has been

refactoring some of the webrtcsink and webrtcsrc code to make it easier to

add more signaller implementations. You can find out more about this work in

his talk at GstConf 2023

and we’ll be writing more about the ongoing effort here as well.

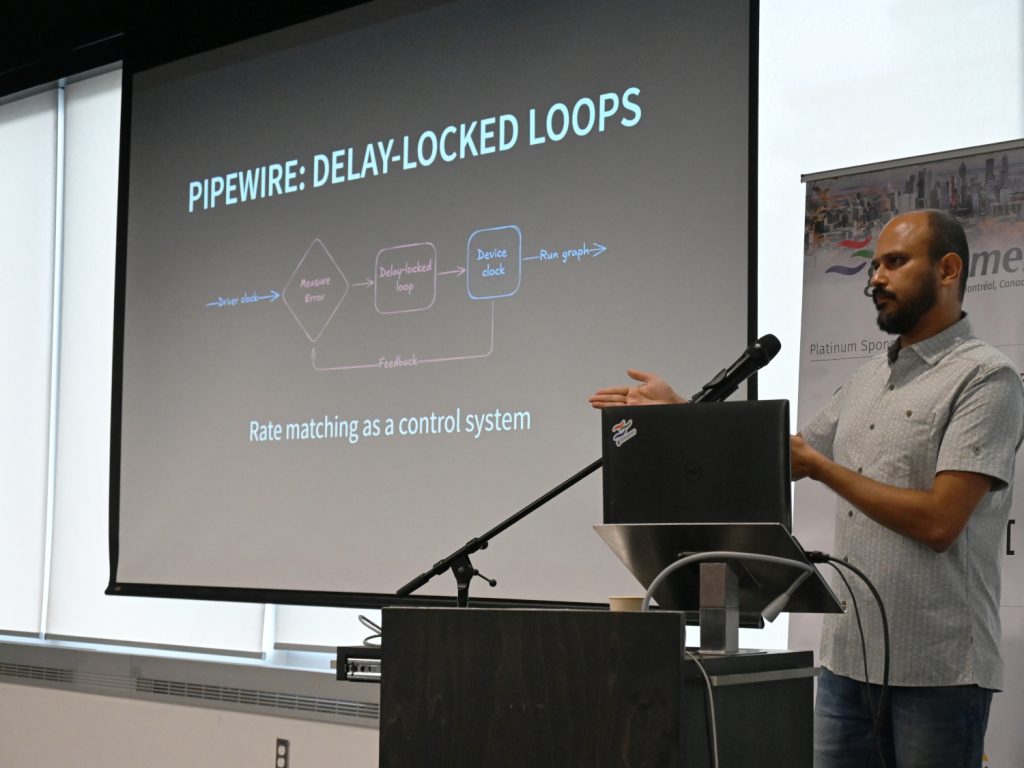

Low-latency embedded audio with PipeWire

Some of our work involves implementing a framework for very low-latency audio

processing on an embedded device. PipeWire is a good fit for this sort of

application, but we have had to implement a couple of features to make it work.

It turns out that doing timer-based scheduling can be more CPU intensive than

ALSA period interrupts at low latencies, so we implemented an IRQ-based

scheduling mode for PipeWire. This is now used by default when a pro-audio

profile is selected for an ALSA device.

In addition to this, we also implemented rate adaptation for USB gadget devices

using the USB Audio Class “feedback control” mechanism. This allows USB gadget

devices to adapt their playback/capture rates to the graph’s rate without

having to perform resampling on the device, saving valuable CPU and latency.

There is likely still some room to optimise things, so expect to more hear on

this front soon.

Compress offload in PipeWire

Sanchayan has written about the work we did

to add support in PipeWire for offloading compressed audio.

This is something we explored in PulseAudio (there’s even an implementation

out there), but it’s a testament to the PipeWire design that we were able to

get this done without any protocol changes.

This should be useful in various embedded devices that have both the hardware

and firmware to make use of this power-saving feature.

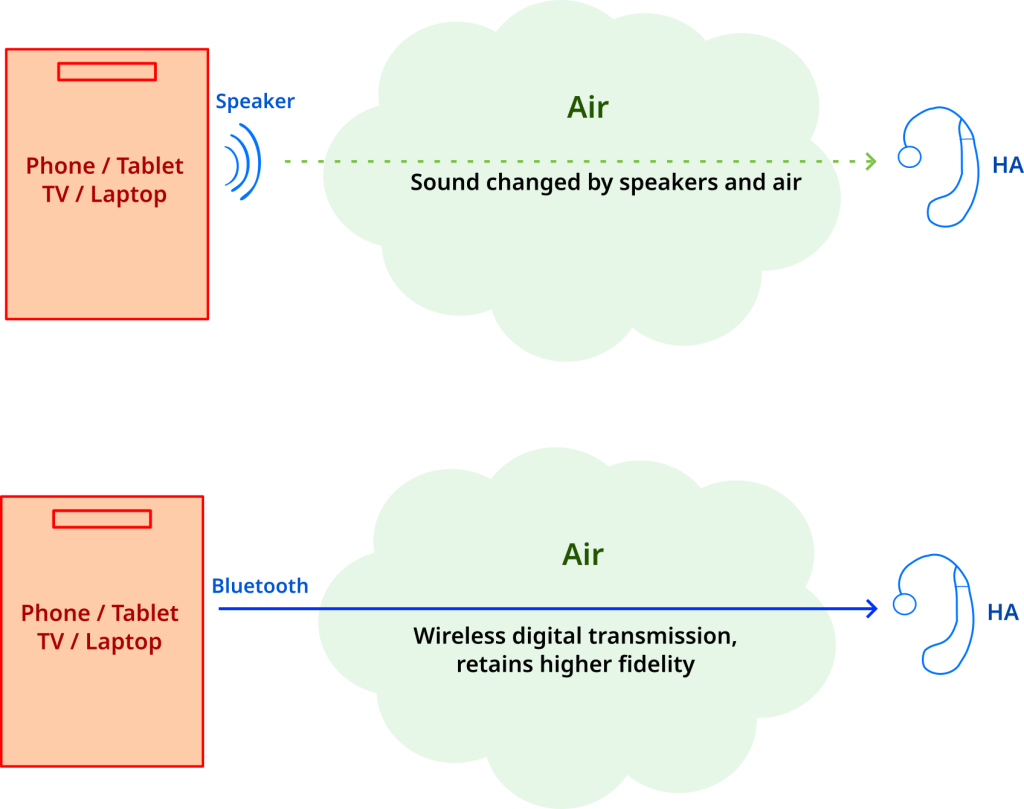

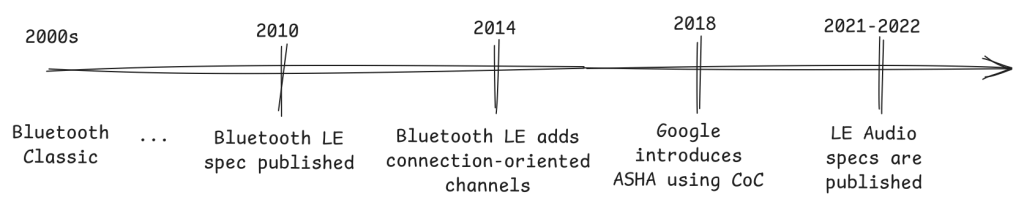

GStreamer LC3 encoder and decoder

Tarun wrote a GStreamer plugin implementing the LC3 codec

using the liblc3 library. This is the

primary codec for next-generation wireless audio devices implementing the

Bluetooth LE Audio specification. The plugin is upstream and can be used to

encode and decode LC3 data already, but will likely be more useful when the

existing Bluetooth plugins to talk to Bluetooth devices get LE audio support.

QUIC plugins for GStreamer

Sanchayan implemented a QUIC source and sink plugin in

Rust, allowing us to start experimenting with the next generation of network

transports. For the curious, the plugins sit on top of the Quinn

implementation of the QUIC protocol.

There is a merge request open

that should land soon, and we’re already seeing folks using these plugins.

AWS S3 plugins

We’ve been fleshing out the AWS S3 plugins over the years, and we’ve added a

new awss3putobjectsink. This provides a better way to push small or sparse

data to S3 (subtitles, for example), without potentially losing data in

case of a pipeline crash.

We’ll also be expecting this to look a little more like multifilesink,

allowing us to arbitrary split up data and write to S3 directly as multiple

objects.

Update to webrtc-audio-processing

We also updated the webrtc-audio-processing

library, based on more recent upstream libwebrtc. This is one of those things

that becomes surprisingly hard as you get into it — packaging an API-unstable

library correctly, while supporting a plethora of operating system and

architecture combinations.

Clients

We can’t always speak publicly of the work we are doing with our clients, but

there have been a few interesting developments we can (and have spoken about).

Both Sanchayan and I spoke a bit about our work with WebRTC-as-a-service

provider, Daily. My talk at the GStreamer Conference

was a summary of the work I wrote about previously

about what we learned while building Daily’s live streaming, recording, and

other backend services. There were other clients we worked with during the

year with similar experiences.

Sanchayan spoke about the interesting approach to building

SIP support

that we took for Daily. This was a pretty fun project, allowing us to build a

modern server-side SIP client with GStreamer and SIP.js.

An ongoing project we are working on is building AES67 support using GStreamer

for FreeSWITCH, which essentially allows

bridging low-latency network audio equipment with existing SIP and related

infrastructure.

As you might have noticed from previous sections, we are also working on a

low-latency audio appliance using PipeWire.

Retrospective

All in all, we’ve had a reasonably productive 2023. There are things I know we

can do better in our upstream efforts to help move merge requests and issues,

and I hope to address this in 2024.

We have ideas for larger projects that we would like to take on. Some of these

we might be able to find clients who would be willing to pay for. For the ideas

that we think are useful but may not find any funding, we will continue to

spend our spare time to push forward.

If you made this this far, thank you, and look out for more updates!